ISSN: 2206-7418

Nanotheranostics 2025; 9(2):110-120. doi:10.7150/ntno.108320 This issue Cite

Review

Metabolomics for the Identification of Biomarkers in Kidney Diseases

University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Received 2024-12-6; Accepted 2025-2-8; Published 2025-3-24

Abstract

With the apparent rise in lifestyle-related changes, there has been a significant decline in renal health. Metabolomics plays a crucial role in the prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment of various renal conditions, including chronic kidney disease, acute kidney injury, diabetic kidney disease, kidney cancer, and post-transplant complications. Metabolomics has identified novel biomarkers, providing insights into altered pathways and potential therapeutic targets for kidney diseases. Kidney diseases and metabolomics keywords were searched in correspondence with the assigned keywords, including chronic kidney diseases, acute kidney injury, kidney carcinoma, kidney transplant, and diabetic kidney diseases on literature search engines. The applicable studies from this search were extracted and included in the study. This review is focused on the biomarkers identified in different kidney diseases such as chronic kidney diseases, acute kidney injury, diabetic kidney disease, kidney carcinoma and kidney transplant.

Keywords: metabolomics, diabetes, kidney, cardiovascular, critical illness

Introduction

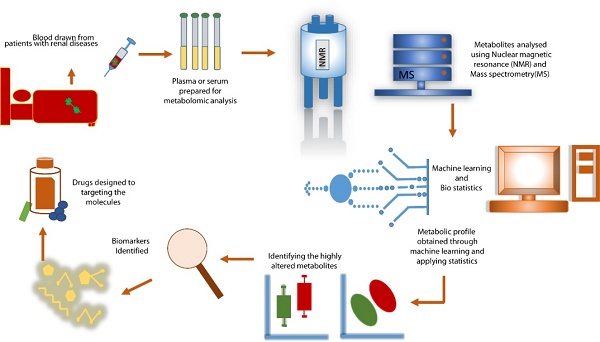

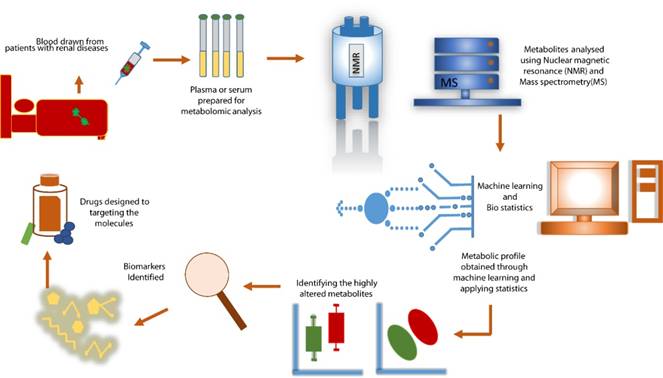

Omics sciences have recently evolved into the most potent approach for identifying biomarkers for various diseases, from lifestyle disorders like diabetes and obesity to nephropathy to critical illnesses such as sepsis 1-13. The molecular approach following these metabolites would give a broader picture of the role of these metabolites in various pathways in multiple diseases 14, 15. Metabolomics provides insight into the pathophysiological mechanism of the broad spectrum of renal diseases (acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, diabetic nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, renal carcinoma, and kidney transplant) 15,16 (Figure 1). Metabolomics could aid in management of the complex kidney conditions (Figure 2). An estimated 700 million individuals worldwide are living with CKD17.Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a significant global health concern, particularly prevalent among hospitalized patients. In pediatric trauma patients in Malawi, AKI occurs in up to 10% of admissions, increasing the risk of death sevenfold compared to those without AKI 18.DKD is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the U.S., accounting for about 50% of new cases19.Kidney cancer accounts for approximately 2% of global cancer diagnoses and deaths. In 2020, there were about 400,000 new cases and 180,000 deaths attributed to renal cell carcinoma worldwide20.In 2019, the U.S. performed a record 24,273 kidney transplants, with approximately 72% from deceased donors. As of December 2018, there were 229,887 patients in the U.S. with a functioning kidney transplant, representing a 40% growth since 200821.

Metabolomics is not yet fully integrated into routine clinical nephrology. A review can advocate for its broader adoption by summarizing the benefits and potential applications in diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized treatments. It can identify gaps in research, such as limitations in biomarker discovery, challenges in clinical translation, or areas where metabolomics has been underutilized, guiding future studies. This review focuses on the application of metabolomics in kidney diseases, which encompass conditions such as acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, diabetic nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, renal carcinoma, and complications arising from kidney transplantation. By elucidating the metabolic alterations associated with these diseases, metabolomics offers valuable insights into pathophysiological mechanisms, aiding in the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of complex renal conditions.

The purpose of this review is threefold: (1) to summarize recent advances in the identification of biomarkers for various kidney diseases using metabolomics, (2) to highlight gaps and challenges in the current research landscape, and (3) to propose future directions for leveraging metabolomics to improve clinical outcomes. By synthesizing findings from a wide range of studies, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how metabolomics can address unmet needs in renal disease research and patient care. Furthermore, this review emphasizes the translational potential of metabolomic biomarkers in paving the way for personalized medicine in nephrology.

Metabolomics Workflow in Kidney Diseases. The metabolomics approach measures metabolic responses in patients with kidney diseases using biological fluids like serum. Advanced analytical techniques, such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS), are utilized to detect and quantify metabolites. Statistical analysis of the data identifies target metabolites associated with kidney conditions, aiding in the understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic interventions.

Clinical Applications of Metabolomics in Kidney Diseases. Metabolomics plays a pivotal role in advancing kidney disease research and management. Its applications include identifying biomarkers for early detection, differentiating between disease types (e.g., CKD, AKI, DKD), predicting disease progression, and monitoring responses to therapy. Additionally, metabolomics contributes to uncovering molecular pathways involved in kidney disease pathophysiology, enabling precision medicine and improved patient care.

Chronic Kidney Disease

There are several potential biomarkers of diagnostic and prognostic potential reported for chronic kidney disease (CKD) such as alanine, valine, glutamine, glycine, arginine, proline, glucose, lactate, succinate, fumarate, betaine, myoinositol, taurine, TMAO, glycerophosphocholine, indoxyl sulfate, adenosine monophosphate (AMP), and guanosine monophosphate (GMP) 22-24.

Untargeted metabolomics performed on large-scale studies involving 1-5 stages of CKD and healthy control enlisted taurine, tiglylcarnitine, canavaninosuccinate, acetylcarnitine, and 5-MTP, as potential biomarkers 25. Among these, 5-MTP was reported to be closely related to the development and progression of kidney disease. Moreover, 5-MTP as a therapeutical target enhanced the keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway and suppressed the IκB/NF-κB signaling pathway 25. Major differences in metabolite profiles with increasing stage of CKD were observed, including altered arginine metabolism, elevated coagulation/inflammation, impaired carboxylate anion transport, and decreased adrenal steroid hormone production.26.

One of the after-effects of CKD is reduced sensitivity to insulin. A study involving 95 non-diabetic patient plasma samples who had undergone hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp 27 illustrated tryptophan metabolism, TCA cycle, and ubiquinone biosynthesis as primary aberrations between CKD and control.

Zhang et al. identified biomarkers of CKD such as including lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) (18:2), cytosine, stearic acid, ricinoleic acid, arginine acid, LPA (16:0) and 3-methylhistidine 28. Apart from serum creatinine, nine other metabolites can predict CKD better 29. Of these, choline and citrulline were identified as markers of kidney metabolism30. D-asparagine and D-serine were reported to be highly related to CKD progression.

Another aspect of imbalance in renal osmotic pressure regulation would increase renal cell damage, aggravating CKD. Hence, increased urinary inositol and betaine levels are prognostic markers for CKD progression31. Another study performed in the African American population identified 5-oxo proline and 1,5-anhydroglucitol to be correlated with a lower risk of CKD 32,33.

Goek et al. identified spermidine and some metabolite ratios such as phosphatidylcholine diacyl C42:5-to-phosphatidylcholine acyl-alkyl C36:0 ratio and kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio to be associated with glomerular filtration rate 34.

The TCA cycle intermediates play an important role in CKD. Hallan et al. identified urinary TCA intermediates such as succinate and isocitrate, to be decreased by 40-68%, while 2-oxoglutarate and citrate excretion was significantly increased in patients with CKD 35.

Another study including three cohorts: a Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study, an African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK), and an Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) analysis was performed to identify pseudouridine, methylimidazoleacetate, and homocitrulline -- associated with CKD progression in CRIC, AASK, and ARIC. Three kynurenine derivatives, namely, 2-aminobenzoic acid, xanthurenic acid, and hydroxypicolinic acid, were upregulated in ESRD compared to CKD with the progression of CKD to ESRD 36.

List of potential biomarkers of diagnostic and prognostic potential reported for chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| Metabolite Class | Biomarker | Type | Metabolic Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids | Alanine | Diagnostic/Prognostic | Protein metabolism |

| Valine | Diagnostic/Prognostic | Branched-chain amino acid metabolism | |

| Glutamine | Diagnostic/Prognostic | Nitrogen metabolism | |

| Glycine | Diagnostic/Prognostic | One-carbon metabolism | |

| Arginine | Diagnostic/Prognostic | Urea cycle | |

| Proline | Diagnostic/Prognostic | Protein metabolism | |

| Energy Metabolites | Glucose | Diagnostic | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Lactate | Diagnostic | Anaerobic metabolism | |

| TCA Cycle Intermediates | Succinate | Diagnostic | Energy metabolism |

| Fumarate | Diagnostic | Energy metabolism | |

| Osmolytes | Betaine | Diagnostic | Methionine metabolism |

| Myoinositol | Diagnostic | Osmotic regulation | |

| Taurine | Diagnostic | Sulfur metabolism | |

| Gut Microbiome-Derived | TMAO | Prognostic | Gut microbiome metabolism |

| Phospholipid-Related | Glycerophosphocholine | Diagnostic | Membrane metabolism |

| Uremic Toxins | Indoxyl sulfate | Prognostic | Protein metabolism |

| Nucleotides | AMP | Diagnostic | Purine metabolism |

| GMP | Diagnostic | Purine metabolism |

Zhu et al. performed metabolomics evaluation of patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease before dialysis, maintenance hemodialysis, and peritoneal dialysis to identify 20 discriminating metabolites screened from the group comparisons, including 2-keto-D-gluconic acid, kynurenic acid, s-adenosylhomocysteine, L-glutamine, adenosine, and nicotinamide37.

Works of Peng et al. identified metabolites highly correlated with kidney function, ranked from the highest down 38. These features were creatinine, N-acetylglucosamine/N-acetylgalactosamine, corticosterone, cis-3,4-methyl gamma-glutamylglutamine, 7-methylguanine, alanine, phenylalanylhydroxyproline, hydroxyasparagine, gamma-glutamyl-isoleucine, undecylenoyl carnitine (C11:1), trimethylamine N-oxide, N-acetylserine, sphingomyelin (d18:0/18:0, d19:0/17:0), pseudouridine, epiandrosterone sulfate, 5-methylthioribose, glutamine_degradant, 1-(1-enyl-palmitoyl)-2-arachidonoyl-GPC (P-16:0/20:4), 5,6-dihydrouridine, N6-carbamoylthreonyladenosine, N,N-dimethyl-pro-pro, 1-methylguanidine, retino (vitamin A), 3-(3-amino-3-carboxyproxypropyl)uridine, erythronate, 1-(1-enyl-palmitoyl)-GPC (P-16:0), gulonate, arabitol/xylitol, and C-glycosyltrptophan.

L-serine, Galacturonic acid, L-glutamine and lower concentrations of Pseudo uridine penta-tms, Butanoic acid, 2,4-bis[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]-, trimethylsilyl ester, 2-O-Glycerol-.alpha.-d-galactopyranoside, hexa-TMS, Myo-inositol, p-cresol, Lactose were significantly altered in patients who did not survive CKD39. Yong et al. identified that trimethylamine N-oxide delays the CKD 40.

Lipidomics helped in the identification of lipids altered in CKD and its progression. Glycerophospholipids, glycerolipids, and total fatty acids in serum were positively related to the increase in serum triglycerides and negatively associated with eGFR 41. Renal tubular epithelial cells were the main site of toxin-induced lipid accumulation, and lipidomics showed that turn-over effectively reduced the levels of phosphatidylcholines, triglycerides, and phosphatidylethanolamines in nephropathy, providing novel insights into the underlying mechanism of toxin-induced lipotoxicity in renal tubular epithelial cells 42. Metabolomics using Nuclear magnetic resonance reported Metabolomics using Nuclear magnetic resonance very-low-density lipoproteins, high-density lipoproteins, the lipid concentration and composition within these lipoproteins, triglycerides within all the lipoprotein subclasses, fatty acids, amino acids, and inflammation biomarkers were associated with CKD risk 43.

Acute Kidney Injury

In a study with patients who received transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) 44, that included AKI patients as per the definition 45,46. The study had a total of 44 patients, 22 with CKD and nine developed AKI. The study reported that baseline levels of 5-adenosylhomocysteine predicted AKI after TAVR, despite adjustment for baseline glomerular filtration rate. Another study involving 2164 patients identified six metabolites that correlated with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 47. Lastly, 5--adenosylhomocysteine was identified to correlate with the dynamic changes in serum creatinine and the predictive potential for AKI. The AKI probability increased with the increase of 5- adenosylhomocysteine.

A single-center study by Zhang et al. on kidney transplant48 states that of the 42 transplants, 22 had developed AKI. Targeted metabolomic analysis was performed to identify tryptophan and arginine as highly altered. Tryptophan concentration was lower in AKI patients than in transplant patients without AKI. The prediction analysis identified Symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) and tryptophan together with an AUC of 0.9.

The LC-MS/MS-based non-targeted metabolomics method was used to differentially screen serum and urine metabolites of acute kidney injury (AKI) patients and healthy people by Chen et al. 49. Blood and urine were collected from 30 AKI subjects and 20 healthy controls. Urine profiling identified 2-S-glutathione glutathione acetate, 5-l-glutamyl-taurine, and l-phosphoarginine with a positive correlation for serum creatinine.

Vancomycin-associated AKI (VAKI) was studied by Lee et al., including the study group along with patients who received vancomycin for infection control but who did not acquire AKI (non-VAKI), chronic kidney disease subjects, and 23 healthy persons 50. Serotonin (5-HT) and 5-hydroxy indole acetic acid (5-HIAA) were significantly higher and lower in the VAKI group than in the non-VAKI groups, respectively.

Another study established the 5-HIAA/5-HT ratio as a biomarker for VAKI 51. The study was performed in urine samples of 159 coronary artery bypass surgery patients to identify the metabolites predictive of developing AKI post-cardiac surgery subjects. AKI predictive metabolites were identified such as tyrosyl-gamma-glutamate, deoxycholic acid glycine conjugate, 5-acetylamino-6-amino-3- methyluracil, arginyl-arginine, and L-methionine.

Urine samples were collected from children: pre-AKI, established AKI and controls 52,53. Another study in pediatric ICU patients was performed to identify biomarkers for early diagnosis and grading 54. The urine samples were collected a maximum of three days post admission until days 5 or 14. The study revealed 20 metabolites as pre AKI and 13 metabolites with great potential for AKI prediction upto three days before AKI onset.

Gisewhite et al. utilized nuclear magnetic resonance to identify mortality/RRT (renal replacement therapy) and AKI stage. They identified metabolites that were correlated with mortality and AKI 1-Methylnicotinamide was common in all the outcomes and highest as the mortality outcomes. Lactate and 1-methyl nicotinamide levels were found in adverse AKI stages and RRT whereas glycine was reported to be associated with survival that did not require RRT 55.

Sun et al. demonstrated that at the early stage of RRT, serum metabolic biomarkers might differentiate patients with a high risk of mortality or permanent kidney injury from those who can recover 56. In the early days 1-arachidonoyl-lysoPC and 1-eicosatetraenoyl-lysoPC were significant. Jun et al. performed a meta-analysis to reveal that more intense RRT was independent of mortality risk 57.

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Early biomarkers with the potential to identify the onset of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) would aid in preventing or delaying the DKD progression. Various metabolomics techniques have been used to investigate and identify the biomarkers of DKD, providing insight into the metabolic pathways obliterated, leading to the development of DKD. The following helps characterize the biomarkers of DKD.

Besides mass spectrometry, people use nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to perform metabolic studies. One of the NMR-based studies reports that lower levels of leucine and isoleucine are found in baseline eGFR patients with type 2 58 BCAA is identified as a prognosis marker in type 1 diabetes 59. Whereas Leucine and valine were identified as mortality markers in patients with diabetes 60. Metabolites associated with a low and high risk of rapid eGFR decline are glycine and n-acetlythreonine, respectively 61,62. 3-hydroxybutyrate is an important metabolite in DKD and ESKD 63,64.

Organic acids like uracil were altered in urine samples of patients with DKD 63,65. The urinary albumin-creatinine ratio increased in patients with T2D 62 and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) 66,67. Alpha-hydroxybutyrate is positively associated with insulin resistance and diabetes but negatively associated with ESKD in patients with diabetes 66. Aliphatic amino acids such as glycine are found to have decreased levels in patients with DKD 68, along with glycolic acid associated with ESKD 63,64,68. Acetoacetate is reported to be negatively associated with baseline eGFR in patients with diabetes, and methyl acetoacetate was reduced in patients with DKD 63. The organic acids mentioned above are involved in energy metabolism, suggesting a dysregulation of mitochondrial function in DKD.

A higher level of SDMA has been found in people with DKD 69. The ratio of SDMA to ADMA is predictive of the decline of kidney function in diabetes 70,71. At the same time, ADMA has been associated with rapid kidney function decline in diabetes 71.

Aromatic amino acids like tryptophan and kynurenine are reported to be obliterated in DKD 61,62,66,67,70,72. Pawlak et al. said that the upregulation of tryptophan metabolism is correlated with impaired kidney function 73. High serum levels of tryptophan are inversely correlated with rapid eGFR decline in patients with DKD 61,70. Likewise, elevated levels of downstream metabolites of tryptophan were directly associated with DKD 62,66,67.

Lipoproteins like HDL (High-density lipoproteins) in relation to baseline eGFR were studied in several diabetic cohorts using NMR, illustrating that they are associated with a higher baseline of eGFR. On the contrary, triglycerides-rich lipoproteins were inversely correlated with albuminuria 58,74. A study involving the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium (n = 188,577) and the CKD Genetics Consortium (n = 133,814) reported that HDL cholesterol was associated lower risk of CKD 75.

Phospholipids such as Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) have been reported with DKD. In a case-control study, they reported a lower level of PCs in patients with diabetes and CKD76. Another survey by Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) stated that serum PCs is predictive of CKD in diabetic patients 77. Unsaturated PEs could differentiate between the progressors and non-progressors of diabetes kidney disease in patients with diabetes 78.

Higher ceramide metabolites have been demonstrated in patients with DKD 76,79. Similarly, elevated levels of sphingomyelin are found in patients with DKD 80, progression of DKD in patients with diabetes81, and chances of developing CKD in hyperglycemic patients77.

Afshinnia et al. reported that in patients with diabetes and baseline eGFR, FFAs are associated with a lower risk of eGFR reduction78. Β-oxidation of Fatty acids results in acylcarnitines, which are elevated in DKD76. Independent of other risk factors, C-16 acylcarnitines are among the strongest predictors of fast eGFR decline in patients with diabetes and CKD70. As with the amino acids, dysregulation of lipid metabolism indicates disturbed energy metabolism, thus mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of DKD.

Early biomarkers with the potential to identify the onset of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) would aid in preventing or delaying DKD progression. Metabolomics has proven instrumental in identifying these early-stage biomarkers, which provide crucial insights into disrupted metabolic pathways long before significant clinical manifestations appear. By utilizing techniques such as mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), researchers have detected alterations in amino acids, organic acids, lipids, and other metabolites that signal the early onset of DKD. For example, lower levels of leucine and isoleucine, markers of impaired mitochondrial function, have been observed in baseline eGFR patients with type 2 diabetes, while metabolites such as glycine and N-acetylthreonine have been linked to rapid declines in renal function.

The ability of metabolomics to reveal these biomarkers facilitates timely intervention strategies, enabling healthcare providers to implement targeted therapies and lifestyle modifications to mitigate disease progression. Furthermore, the identification of dysregulated pathways--such as those related to energy metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammation--provides opportunities to develop novel therapeutic targets. This proactive approach underscores the potential of metabolomics not only in diagnosing DKD but also in informing preventive measures and personalized treatment plans, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Kidney Carcinoma

Pyruvate is converted to lactate in RCC patients, contrary to healthy control 82. These metabolites were also elevated in tumor tissues 83-85 and urine samples 86. Priolo et al. identified fumarate, malate, and citrate as potential biomarkers in 87, 88,89.

Glutathione is elevated in cancer progression 90, including RCC 91. Hakimi et al. studied that patients with high glutathione levels were likely to progress into advanced stages. Apart from that α-hydroxybutyrate, it was significant in distinguishing stage II patients. Since the role of glutathione metabolism impairment is critical in the pathogenesis of RCC, this could be targeted for therapeutics 87.

Apart from glutathione, glutamine is also elevated in renal tissues 83. Fu et al. targeted the RCC with elevated glutamine as the therapeutic target to establish that Interleukin 23 (IL-23) enhanced cancer metastasis via elevated regulatory T cells 92. Patients with high IL-23 had a lower survival rate than patients with lower IL-23 92. Glutaminase inhibitor (CB-839) is being utilized for RCC treatment with good efficacy 93. Work by Gao et al. reported that amino acids like alanine and valine were decreased in RCC patients.

Alanine, choline, creatine, lactate, isoleucine, leucine, and valine had diagnostic potential for RCC, and the efficacy of these amino acids was validated in 22 additional independent subjects 82. Apart from these amino acids, metabolites of this amino acid metabolism, such as dentist acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, and quinolinic acid, were altered in the urine samples of RCC patients 94.

Liu et al. identified a 1.67 and 2.07-fold increase in the levels of N-formylkynurenine in healthy control and benign tumors, respectively, identifying its potential as a biomarker for distinguishing RCC, benign renal tumors, and healthy control 95.

Vitamin E has been implicated in RCC prognosis 96. Sobotka et al. the prognostic potential of Vitamin E by studying 102 RCC patients and establishing an inverse relationship between survival and vitamin E 97. Similarly, Vitamin D has been shown to be associated with a lower risk for RCC in a study with 46,380 men and 72,051 women 98.

Sheila et al. identified various acylcarnitines to be closely associated with RCC grade. Acylcarnitines were reported to be upregulated in the urine of patients with high-grade cancer 99. Another study supported the role of acylcarnitine in RCC by demonstrating the elevated levels of acylcarnitine in the tissue and urine of RCC patients 100. RCC progression involves choline metabolism, as reported by Lin et al. 101, 102.

Ragone et al. identified that hippuric acid was decreased in the urine samples of RCC patients compared to the control 86. Yoshimura et al. established a novel diagnostic approach by utilizing electrospray ionization/ mass spectrometry to detect the boundary of cancerous regions by identifying the expression of triacylglycerols in 9 RCC patients 103.

Kidney Transplantation

The development of minimally invasive method for kidney function in transplant is necessary. Hence, the metabolomics approach would be an appropriate one. Iwamoto et al. analyzed kidney transplant recipients' plasma, saliva, and urine 104. The study identified metabolic aberrations in T cell-mediated rejection (TCR), antibody-mediated rejection, and other kidney disorders (KD). The three biofluids showed different metabolic patterns between T cell-mediated rejection (TCR) and kidney disorders (KD), with 3-indoxyl sulfate showing a significant increase in TCR plasma and urine samples. The study demonstrated that 3-indoxyl sulfate had the potential to predict acute rejection. Urinary metabolomics for non-invasivenon-invasive detection of antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) identified proline, citrulline, phosphatidylcholine aa.C34.4, C10.2, and tetradecanoylcarnitine as diagnostic markers for AMR105.

Ivana et al. performed serum metabolomics in 19 individuals who received kidney transplants and collected samples before and after transplantation. The study identified hippurate, mannitol, and alanine as associated with the changes in renal function during the post-transplantation recovery period106. Colas et al. performed metabolomic studies in spontaneous tolerant kidney transplants that are long-term and functional grafts without immunosuppressive drug intake to identify tryptophan-derived metabolites such as kynurenic acid and tryptamine, characterizing the operational tolerance 107.

Dedinska et al. aimed to help with the non-invasive-invasive diagnosis of graft rejection due to T-cell activation by identifying metabolites reflecting the activation of T cells such as glutamine, lactate, tyrosine, and branched chain α keto acids (BCKAs)108. In all, a panel of nine differential metabolites was identified as novel potential metabolite biomarkers of T- cell-mediated rejection 109. Liu et al. performed a multicenter study to detect metabolites in perfusate collected at the beginning and end of deceased-donor kidney perfusion and evaluated their associations with graft failure. Alpha-ketoglutarate, 3-carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropanoate, 1-carboxyethyl phenylalanine, and three glycerolphosphatidylcholineswere found to be associated with increased graft rejection.110.

The kidney graft recovery process can be examined noninvasively by studying urine samples 111. Urinary metabolome of donation after circulatory death (DCD) transplant recipients. Revealed that branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) over pyroglutamate and lactate over fumarate predicted prolonged functional delayed graft rejection (PDGF) 105. Chronic kidney allograft damage is characterized by arginine, histidine, proline, and SDMA 112. The lower level of serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate was found in the acute graft rejection group before transplantation113.

The assessment of kidney function within the first year following transplantation was performed via metabolomics using the non-targeted approach114. Nineteen metabolites were found to differ significantly in the 1st week and seventeen in the 3rd month; no significant differences were observed in the 6th month115. Metabolomic profiling in individuals with a failing kidney allograft revealed choline, creatine, taurine, and threonine in individuals with lower GFR116.

Untargeted analysis of feces was performed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify difference between kidney transplant and control group. The fecal metabolome was high in sterols and fatty acids in the stable transplant group 117.

Intestinal microbiome and metabolome analyses reveal metabolic disorders in the early stage of renal transplantation118,119. Enterococcus was found to be correlated with renal functions and metabolites reflecting renal damage 120.

Key Metabolomic Biomarkers for Kidney Function

Following are the list of about some diagnostic biomarkers related to Kidney function impairments identified and established using metabolomics approach.

A. Tryptophan Metabolism Pathway

1. Kynurenine

2. Kynurenic acid

3. 3-indoxyl sulfate

These metabolites are typically elevated in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and correlate with disease progression34,36,73.

B. Gut Microbiome-Derived Metabolites

1. p-cresyl sulfate

2. Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO)

Indoxyl sulfate

These are uremic toxins that accumulate in kidney dysfunction 22,23,113.

C. Acylcarnitines

1. Long-chain acylcarnitines

2. Short-chain acylcarnitines

Altered levels indicate disturbed fatty acid oxidation in kidney disease70,99.

D. Amino Acid-Related

1. Symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA)

2. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)

These are particularly useful for early detection of kidney dysfunction70,71.

Future Directions

The field of metabolomics is poised for significant advancements, driven by innovations in technology and computational tools. One promising avenue is the integration of machine learning (ML) with metabolomics data analysis. ML algorithms can process vast and complex datasets, uncovering subtle patterns and relationships that might otherwise remain undetected. This approach holds immense potential for refining biomarker discovery, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, and predicting disease progression with greater precision.

Another transformative development is single-cell metabolomics, which enables the analysis of metabolic profiles at the individual cell level. This technology could revolutionize kidney research by providing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity and the microenvironment within renal tissues. For instance, single-cell metabolomics could help identify cell-specific metabolic alterations in kidney diseases, offering new perspectives on pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets.

Additionally, advancements in real-time metabolomics and portable analytical devices may enable point-of-care testing, facilitating rapid and non-invasive diagnostics. The development of more sensitive and high-throughput platforms will also expand the scope of metabolomics studies, allowing for the comprehensive profiling of low-abundance metabolites and their dynamic changes during disease progression.

These technological innovations, combined with interdisciplinary collaboration and the growth of metabolomics databases, are set to propel the field forward. By leveraging these advancements, kidney research can move closer to achieving precision medicine, where interventions are tailored to the unique metabolic signatures of individual patients.

Limitations

Despite its significant potential, metabolomics research faces several limitations that must be addressed to maximize its utility in kidney disease research. One major challenge is the small sample size of many studies, which limits the generalizability of findings and increases the risk of statistical bias. Expanding sample sizes and ensuring adequate statistical power are critical for deriving robust and reproducible results.

Population diversity is another limitation, as many metabolomics studies are conducted in homogenous populations that do not reflect global demographic and genetic variability. This lack of diversity hinders the applicability of findings to broader populations and underscores the need for more inclusive and representative study cohorts.

Reproducibility remains a persistent challenge in metabolomics research due to variations in experimental protocols, sample handling, and data analysis methods. Standardizing workflows, from sample preparation to data processing, is essential for improving reproducibility and enabling cross-study comparisons.

Additionally, metabolomics studies often struggle with the complexity of metabolite identification and quantification. Many metabolites remain unannotated, and their biological significance is poorly understood. Addressing this limitation will require advancements in computational tools, databases, and collaborative efforts to improve metabolite annotation and pathway mapping.

By addressing these limitations, future metabolomics studies can achieve greater reliability and impact, ultimately enhancing their contribution to understanding and managing kidney diseases.

Conclusion

Metabolomics has provided great insight into many candidate metabolites appropriate as biomarkers for several kidney diseases and for deciphering the onset and progression of the diseases. Most metabolites and their pathways are linked to oxidative stress and inflammation. These interpretations are limited, many features remain unidentified. As the database grows, we can interrogate it further to understand kidney diseases. Clinicians can leverage metabolomics not only for diagnosis and treatment but also as a tool to enhance patient outcomes through early interventions, precision medicine, and a better understanding of disease mechanisms. By integrating these findings into clinical workflows, metabolomics has the potential to transform nephrology practice.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Pandey S, Adnan Siddiqui M Fau - Azim A, Azim A Fau - Trigun SK, Trigun Sk Fau - Sinha N, Sinha N. Serum metabolic profiles of septic shock patients based upon co-morbidities and other underlying conditions. Mol Omics. 2021;17(2):260-276

2. Pandey S, Azim A, Sinha N. Longitudinal NMR Based Serum Metabolomics to Track the Potential Serum Biomarkers of Septic Shock. Nanotheranostics. 2023;7(2):142-151 doi:10.7150/ntno.79394

3. Pandey S, Siddiqui MA, Azim A, Sinha N. Metabolic fingerprint of patients showing responsiveness to treatment of septic shock in intensive care unit. MAGMA. 2023Aug;36(4):659-669 doi:10.1007/s10334-022-01049-9

4. Pandey S, Siddiqui MA, Trigun SK, Azim A, Sinha N. Gender-specific association of oxidative stress and immune response in septic shock mortality using NMR-based metabolomics. Mol Omics. 2022Feb21;18(2):143-153 doi:10.1039/d1mo00398d

5. Siddiqui MA, Pandey S, Azim A, Sinha N, Siddiqui MH. Metabolomics: An emerging potential approach to decipher critical illnesses. Biophys Chem. 2020Dec;267:106462 doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2020.106462

6. Krieg L, Didt K, Karkossa I. et al. Multiomics reveal unique signatures of human epiploic adipose tissue related to systemic insulin resistance. Gut. 2022Nov;71(11):2179-2193 doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324603

7. Apostolopoulou M, Gordillo R, Gancheva S. et al. Role of ceramide-to-dihydroceramide ratios for insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in humans. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(2):e001860

8. Hanna MH, Dalla Gassa A, Mayer G. et al. The nephrologist of tomorrow: towards a kidney-omic future. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017Mar;32(3):393-404 doi:10.1007/s00467-016-3357-x

9. Pandey S. Sepsis, Management & Advances in Metabolomics. Nanotheranostics. 2024;8(3):270-284 doi:10.7150/ntno.94071

10. Pandey S. Metabolomics Characterization of Disease Markers in Diabetes and Its Associated Pathologies. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. May 23 2024;doi:10.1089/met. 2024 0038

11. Pandey S. Advances in metabolomics in critically ill patients with Sepsis and Septic Shock. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2024 doi:https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.24.211

12. Pandey S. Metabolomics for the identification of biomarkers in endometriosis. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2024;310(6):2823-2827 doi:10.1007/s00404-024-07796-5

13. Anamika Singh MAS, Pandey S. et al. Unveiling Pathophysiological Insights: Serum Metabolic Dysregulation in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of Proteome Research. 2024;23:4216-4228

14. Zhang YM, Wang YF, Rasheed H, Ott J. Editorial: Multi-Omics Study in Revealing Underlying Pathogenesis of Complex Diseases: A Translational Perspective. Front Genet. 2021;12:789294 doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.789294

15. Wang D, Yang J, Fan J, Chen W, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Li J. Omics technologies for kidney disease research. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2020Oct;303(10):2729-2742 doi:10.1002/ar.24413

16. Fanos V, Fanni C, Ottonello G, Noto A, Dessi A, Mussap M. Metabolomics in adult and pediatric nephrology. Molecules. 2013Apr24;18(5):4844-57 doi:10.3390/molecules18054844

17. Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong ACM. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2024;20(7):473-485 doi:10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6

18. Bjornstad EC, Muronya W, Smith ZH. et al. Incidence and epidemiology of acute kidney injury in a pediatric Malawian trauma cohort: a prospective observational study. BMC Nephrology. 2020;21(1):98 doi:10.1186/s12882-020-01755-3

19. Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017Dec7;12(12):2032-2045 doi:10.2215/CJN.11491116

20. Makino T, Kadomoto S, Izumi K, Mizokami A. Epidemiology and Prevention of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2022 14(16). doi:10.3390/cancers14164059

21. Wang JH, Hart A. Global Perspective on Kidney Transplantation: United States. Kidney360. 2021;2:1836-1839 doi:10.34067/KID.0002472021

22. Zhao YY. Metabolomics in chronic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;422:59-69 doi:10.1016/j.cca.2013.03.033

23. Zhao Yy Fau - Lint R-C, Lint RC. Metabolomics in nephrotoxicity. Adv Clin Chem. 2014;65:69-89

24. Kalim S, Rhee EP. An overview of renal metabolomics. Kidney Int. 2017;91(1):61-69 doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.08.021

25. Chen DQ, Cao G, Chen H. et al. Identification of serum metabolites associating with chronic kidney disease progression and anti-fibrotic effect of 5-methoxytryptophan. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1476 doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09329-0

26. Shah VO, Townsend RR, Feldman HI, Pappan KL, Kensicki E, Vander Jagt DL. Plasma metabolomic profiles in different stages of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(3):363-70 doi:10.2215/CJN.05540512

27. Roshanravan B, Zelnick LR, Djucovic D. et al. Chronic kidney disease attenuates the plasma metabolome response to insulin. JCI Insight. 2018;3(16):e122219

28. Zhang ZH, Chen H, Vaziri ND. et al. Metabolomic Signatures of Chronic Kidney Disease of Diverse Etiologies in the Rats and Humans. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(10):3802-3812 doi:10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00583

29. Rhee EP, Clish CB, Ghorbani A. et al. A combined epidemiologic and metabolomic approach improves CKD prediction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(8):1330-8 doi:10.1681/ASN.2012101006

30. Kimura T, Hamase K, Miyoshi Y. et al. Chiral amino acid metabolomics for novel biomarker screening in the prognosis of chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6(6):26137 doi:10.1038/srep26137

31. Gil RB, Ortiz A, Sanchez-Nino MD. et al. Increased urinary osmolyte excretion indicates chronic kidney disease severity and progression rate. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(12):2156-2164 doi:10.1093/ndt/gfy020

32. Yu B, Zheng Y, Nettleton JA, Alexander D, Coresh J, Boerwinkle E. Serum metabolomic profiling and incident CKD among African Americans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(8):1410-7

33. Rysz J, Gluba-Brzózka A, Franczyk B, Jabłonowski Z, Ciałkowska-Rysz A. Novel Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease and the Prediction of Its Outcome. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8):1702

34. Goek ON, Prehn C, Sekula P. et al. Metabolites associate with kidney function decline and incident chronic kidney disease in the general population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(8):2131-8 doi:10.1093/ndt/gft217

35. Hallan S, Afkarian M, Zelnick LR. et al. Metabolomics and Gene Expression Analysis Reveal Down-regulation of the Citric Acid (TCA) Cycle in Non-diabetic CKD Patients. EBioMedicine. 2017;26:68-77 doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.10.027

36. Dahabiyeh LA, Nimer RM, Sumaily KM. et al. Metabolomics profiling distinctively identified end-stage renal disease patients from chronic kidney disease patients. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):6161 doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33377-8

37. Zhu S, Zhang F, Shen AW. et al. Metabolomics Evaluation of Patients With Stage 5 Chronic Kidney Disease Before Dialysis, Maintenance Hemodialysis, and Peritoneal Dialysis. Front Physiol. 2021;11:630646

38. Peng H, Liu X, Aoieong C. et al. Identification of Metabolite Markers Associated with Kidney Function. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:6190333 doi:10.1155/2022/6190333

39. Sheetal A. Predictive Modeling of Metabolomics data for the Identification of Biomarkers in Chronic Kidney Disease. Medical Research Archives. 2023 11 (6)

40. Hu DY, Wu MY, Chen GQ. et al. Metabolomics analysis of human plasma reveals decreased production of trimethylamine N-oxide retards the progression of chronic kidney disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2022Sep;179(17):4344-4359 doi:10.1111/bph.15856

41. Wang J, Cui Z, Lu J. et al. Circulating Antibodies against Thrombospondin Type-I Domain-Containing 7A in Chinese Patients with Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(10):1642-1651 doi:10.2215/CJN.01460217

42. Yang X, Xu W, Huang K. et al. Precision toxicology shows that troxerutin alleviates ochratoxin A-induced renal lipotoxicity. FASEB J. 2019;33(2):2212-2227

43. Geng TT, Chen JX, Lu Q. et al. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance-Based Metabolomics and Risk of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2024Jan;83(1):9-17 doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.05.014

44. Elmariah S, Farrell LA, Daher M. et al. Metabolite Profiles Predict Acute Kidney Injury and Mortality in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016Mar15;5(3):e002712 doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.002712

45. Kappetein AP, Head Sj Fau - Généreux P, Généreux P Fau - Piazza N. et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(19):2403-18

46. Bagshaw SM, George C, Bellomo R, Committe ADM. A comparison of the RIFLE and AKIN criteria for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008May;23(5):1569-74 doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn009

47. Dawber Tr Fau - Meadors GF, Meadors Gf Fau - Moore FE Jr, Moore FE Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41(3):279-286 doi:D - CLML: 5120:51406:421 OTO - NLM

48. Zhang F, Wang Q, Xia T. et al. Diagnostic value of plasma tryptophan and symmetric dimethylarginine levels for acute kidney injury among tacrolimus-treated kidney transplant patients by targeted metabolomics analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14688

49. Chen C, Zhang P, Bao G, Fang Y, Chen W. Discovery of potential biomarkers in acute kidney injury by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q/TOF-MS). Int Urol Nephrol. 2021Dec;53(12):2635-2643 doi:10.1007/s11255-021-02829-3

50. Lee HA-O, Kim SA-OX, Jang JA-O, Park HA-OX, Lee SA-O. Serum 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic Acid and Ratio of 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic Acid to Serotonin as Metabolomics Indicators for Acute Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Vancomycin-Associated Acute Kidney Injury. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(6):895

51. Tian M, Liu X, Chen L. et al. Urine metabolites for preoperative prediction of acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;165(3):1165-1175 e3. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.03.118

52. Franiek A, Sharma A, Cockovski V, Wishart DS, Zappitelli M, Blydt-Hansen TD. Urinary metabolomics to develop predictors for pediatric acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37(9):2079-2090 doi:10.1007/s00467-021-05380-6

53. Lagos-Arevalo P, Palijan A, Vertullo L. et al. Cystatin C in acute kidney injury diagnosis: early biomarker or alternative to serum creatinine? Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(4):665-76 doi:10.1007/s00467-014-2987-0

54. Palermo J, Dart AB, De Mello A. et al. Biomarkers for Early Acute Kidney Injury Diagnosis and Severity Prediction: A Pilot Multicenter Canadian Study of Children Admitted to the ICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(6):e235-e244 doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001183

55. Gisewhite S, Stewart IJ, Beilman G, Lusczek E. Urinary metabolites predict mortality or need for renal replacement therapy after combat injury. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):119 doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03544-2

56. Sun J, Cao Z, Schnackenberg L. et al. Serum metabolite profiles predict outcomes in critically ill patients receiving renal replacement therapy. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2021;1187:123024 doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2021.123024

57. Jun M, Heerspink HJ, Ninomiya T. et al. Intensities of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(6):956-63 doi:10.2215/CJN.09111209

58. Tofte N, Vogelzangs N, Mook-Kanamori D. et al. Plasma Metabolomics Identifies Markers of Impaired Renal Function: A Meta-analysis of 3089 Persons with Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(7):dgaa173

59. Tofte N, Suvitaival T, Trost K. et al. Metabolomic Assessment Reveals Alteration in Polyols and Branched Chain Amino Acids Associated With Present and Future Renal Impairment in a Discovery Cohort of 637 Persons With Type 1 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:818 doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00818

60. Welsh P, Rankin N, Li Q. et al. Circulating amino acids and the risk of macrovascular, microvascular and mortality outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from the ADVANCE trial. Diabetologia. 2018Jul;61(7):1581-1591 doi:10.1007/s00125-018-4619-x

61. Colombo M, Valo E, McGurnaghan SJ. et al. Biomarker panels associated with progression of renal disease in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2019Sep;62(9):1616-1627 doi:10.1007/s00125-019-4915-0

62. Solini A, Manca ML, Penno G, Pugliese G, Cobb JE, Ferrannini E. Prediction of Declining Renal Function and Albuminuria in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes by Metabolomics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):696-704 doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3345

63. Sharma K, Karl B, Mathew AV. et al. Metabolomics reveals signature of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1901-12 doi:10.1681/ASN.2013020126

64. Kwan B, Fuhrer T, Zhang J. et al. Metabolomic Markers of Kidney Function Decline in Patients With Diabetes: Evidence From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(4):511-520 doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.01.019

65. Lin HA-O, Cheng MA-OX, Lo CA-O, Lin GA-O, Liu FA-O. Metabolomic Signature of Diabetic Kidney Disease in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(11):2626

66. Niewczas MA, Sirich TL, Mathew AV. et al. Uremic solutes and risk of end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes: metabolomic study. Kidney Int. 2014;85(5):1214-24 doi:10.1038/ki.2013.497

67. Niewczas MA, Mathew AV, Croall S. et al. Circulating Modified Metabolites and a Risk of ESRD in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):383-390

68. Li L, Wang C Fau - Yang H, Yang H Fau - Liu S. et al. Metabolomics reveal mitochondrial and fatty acid metabolism disorders that contribute to the development of DKD in T2DM patients. Mol Biosyst. 2017;13(11):2392-2400

69. Hirayama A, Nakashima E, Sugimoto M. et al. Metabolic profiling reveals new serum biomarkers for differentiating diabetic nephropathy. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404(10):3101-9 doi:10.1007/s00216-012-6412-x

70. Looker HC, Colombo M, Hess S. et al. Biomarkers of rapid chronic kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;88(4):888-96 doi:10.1038/ki.2015.199

71. Colombo M, Looker HC, Farran B. et al. Serum kidney injury molecule 1 and β(2)-microglobulin perform as well as larger biomarker panels for prediction of rapid decline in renal function in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2019;62(1):156-168

72. Winther SA-O, Henriksen PA-OX, Vogt JK. et al. Gut microbiota profile and selected plasma metabolites in type 1 diabetes without and with stratification by albuminuria. Diabetologia. 2020;63:2713-2724

73. Pawlak D, Tankiewicz A, Matys T, Buczko W. Peripheral distribution of kynurenine metabolites and activity of kynurenine pathway enzymes in renal failure. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54(2):175-89

74. Barrios C, Zierer J, Würtz P. et al. Circulating metabolic biomarkers of renal function in diabetic and non-diabetic populations. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):15249 doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33507-7

75. Lanktree MB, Thériault S, Walsh M, Paré G. HDL Cholesterol, LDL Cholesterol, and Triglycerides as Risk Factors for CKD: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):166-172

76. Liu JJ, Ghosh S, Kovalik JP. et al. Profiling of Plasma Metabolites Suggests Altered Mitochondrial Fuel Usage and Remodeling of Sphingolipid Metabolism in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes and Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(3):470-480 doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2016.12.003

77. Huang J, Huth C, Covic M. et al. Machine Learning Approaches Reveal Metabolic Signatures of Incident Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals With Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2020;69(12):2756-2765 doi:10.2337/db20-0586

78. Afshinnia F, Nair V, Lin J. et al. Increased lipogenesis and impaired β-oxidation predict type 2 diabetic kidney disease progression in American Indians. JCI Insight. 2019;4(21):e130317

79. Klein RL, Hammad SM, Baker NL. et al. Decreased plasma levels of select very long chain ceramide species are associated with the development of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Metabolism. 2014;63(10):1287-95

80. Mäkinen Vp Fau - Tynkkynen T, Tynkkynen T Fau - Soininen P, Soininen P Fau - Forsblom C. et al. Sphingomyelin is associated with kidney disease in type 1 diabetes (The FinnDiane Study). Metabolomics. 2012;8(3):369-375

81. Pongrac Barlovic D, Harjutsalo V, Sandholm N, Forsblom C, Groop PH, FinnDiane Study G. Sphingomyelin and progression of renal and coronary heart disease in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2020;63(9):1847-1856 doi:10.1007/s00125-020-05201-9

82. Zheng H, Ji J, Zhao L. et al. Prediction and diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma using nuclear magnetic resonance-based serum metabolomics and self-organizing maps. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):59189-59198 doi:10.18632/oncotarget.10830

83. Gao H, Dong B, Jia J. et al. Application of ex vivo (1)H NMR metabonomics to the characterization and possible detection of renal cell carcinoma metastases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138(5):753-61 doi:10.1007/s00432-011-1134-6

84. Dong B, Gao Y, Kang X. et al. SENP1 promotes proliferation of clear cell renal cell carcinoma through activation of glycolysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:80435-80449

85. Lucarelli G, Galleggiante V, Rutigliano M. et al. Metabolomic profile of glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway identifies the central role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in clear cell-renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(15):13371-86 doi:10.18632/oncotarget.3823

86. Ragone R, Sallustio FA-O, Piccinonna S. et al. Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Study through NMR-Based Metabolomics Combined with Transcriptomics. Diseases. 2016;4(1):7

87. Priolo C, Khabibullin D, Reznik E. et al. Impairment of gamma-glutamyl transferase 1 activity in the metabolic pathogenesis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(27):E6274-E6282 doi:10.1073/pnas.1710849115

88. Mignion L, Dutta P, Martinez GV, Foroutan P, Gillies RJ, Jordan BF. Monitoring chemotherapeutic response by hyperpolarized 13C-fumarate MRS and diffusion MRI. Cancer Res. 2014;74(3):686-94 doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1914

89. Shenoy N, Bhagat TD, Cheville J. et al. Ascorbic acid-induced TET activation mitigates adverse hydroxymethylcytosine loss in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(4):1612-1625 doi:10.1172/JCI98747

90. Lien EC, Lyssiotis CA-O, Juvekar A. et al. Glutathione biosynthesis is a metabolic vulnerability in PI(3)K/Akt-driven breast cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(5):572-8

91. Aa Fau H. et al. An Integrated Metabolic Atlas of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(1):104-116

92. Fu Q, Xu L, Wang Y. et al. Tumor-associated Macrophage-derived Interleukin-23 Interlinks Kidney Cancer Glutamine Addiction with Immune Evasion. Eur Urol. 2019;75(5):752-763 doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.030

93. Funda Meric-Bernstam NMT. et al. Phase 1 study of CB-839, a small molecule inhibitor of glutaminase (GLS), alone and in combination with everolimus (E) in patients (pts) with renal cell cancer (RCC). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 34(15)

94. Yen TA, Dahal KS, Lavine B, Hassan Z, Gamagedara S. Development and Validation of High Performance Liquid Chromatographic Method for Determination of Gentisic Acid and Related Renal Cell Carcinoma Biomarkers in Urine. Microchem J. 2018;137:85-89 doi:10.1016/j.microc.2017.09.024

95. Liu X, Zhang M, Liu X. et al. Urine Metabolomics for Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) Prediction: Tryptophan Metabolism as an Important Pathway in RCC. Front Oncol. 2019;9:663

96. Catchpole G, Platzer A, Weikert C. et al. Metabolic profiling reveals key metabolic features of renal cell carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(1):109-18 doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00939.x

97. Sobotka R, Capoun O, Kalousova M. et al. Prognostic Importance of Vitamins A, E and Retinol-binding Protein 4 in Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients. Anticancer Res. 2017Jul;37(7):3801-3806 doi:10.21873/anticanres.11757

98. Joh HK, Giovannucci EL, Bertrand KA, Lim S, Cho E. Predicted plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of renal cell cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(10):726-32 doi:10.1093/jnci/djt082

99. Ganti S, Taylor SL, Kim K. et al. Urinary acylcarnitines are altered in human kidney cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012Jun15;130(12):2791-800 doi:10.1002/ijc.26274

100. Niziol J, Bonifay V, Ossolinski K. et al. Metabolomic study of human tissue and urine in clear cell renal carcinoma by LC-HRMS and PLS-DA. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018;410(16):3859-3869 doi:10.1007/s00216-018-1059-x

101. Lin L, Yu Q, Yan X. et al. Direct infusion mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography mass spectrometry for human metabonomics? A serum metabonomic study of kidney cancer. Analyst. 2010;135(11):2970-8 doi:10.1039/c0an00265h

102. Itoh J, Ito A, Shimada S. et al. Clinicopathological significance of ganglioside DSGb5 expression in renal cell carcinoma. Glycoconj J. 2017;34(2):267-273 doi:10.1007/s10719-017-9763-x

103. Yoshimura K, Chen Lc Fau - Mandal MK, Mandal Mk Fau - Nakazawa T. et al. Analysis of renal cell carcinoma as a first step for developing mass spectrometry-based diagnostics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(10):1741-9

104. Iwamoto H, Okihara MA-O, Akashi I. et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Plasma, Urine, and Saliva of Kidney Transplantation Recipients. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13938

105. Kostidis S, Bank JR, Soonawala D. et al. Urinary metabolites predict prolonged duration of delayed graft function in DCD kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(1):110-122 doi:10.1111/ajt.14941

106. Stanimirova I, Banasik M, Ząbek A. et al. Serum metabolomics approach to monitor the changes in metabolite profiles following renal transplantation. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):17223 doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74245-z

107. Colas L, Royer AL, Massias J. et al. Urinary metabolomic profiling from spontaneous tolerant kidney transplanted recipients shows enrichment in tryptophan-derived metabolites. EBioMedicine. 2022;77:103844 doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103844

108. Dedinska I, Baranovičová E, Graňák K, Vnučák M, Beliančinová M, Mokáň M. MO980: Metabolomics Approach and Acute Rejection in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2022;37(Supplement_3):gfac087.038 doi:10.1093/ndt/gfac087.038

109. Kalantari S, Chashmniam S, Nafar M, Samavat S, Rezaie D, Dalili N. A Noninvasive Urine Metabolome Panel as Potential Biomarkers for Diagnosis of T Cell-Mediated Renal Transplant Rejection. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology. 2020;24(3):140-147 doi:10.1089/omi.2019.0158

110. Liu RX, Koyawala N, Thiessen-Philbrook HR. et al. Untargeted metabolomics of perfusate and their association with hypothermic machine perfusion and allograft failure. Kidney Int. 2023;103(4):762-771 doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.11.020

111. Calderisi M, Vivi A, Mlynarz P. et al. Using metabolomics to monitor kidney transplantation patients by means of clustering to spot anomalous patient behavior. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(4):1511-5 doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.049

112. Landsberg A, Sharma A, Gibson IW, Rush D, Wishart DS, Blydt-Hansen TD. Non-invasive staging of chronic kidney allograft damage using urine metabolomic profiling. Pediatric Transplantation. 2018;22:e13226

113. Zhao X, Chen J, Ye L, Xu G. Serum Metabolomics Study of the Acute Graft Rejection in Human Renal Transplantation Based on Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Proteome Research. 2014;13(5):2659-2667 doi:10.1021/pr5001048

114. Kienana M. Elucidating time-dependent changes in the urinary metabolome of renal transplant patients by a combined 1H NMR and GC-MS approach. Mol BioSyst. 2015;11:2459-2510

115. Yozgat I, Cakir U, Serdar MA. et al. Longitudinal non-targeted metabolomic profiling of urine samples for monitoring of kidney transplantation patients. Ren Fail. 2024;46(1):2300736 doi:10.1080/0886022X.2023.2300736

116. Bassi R, Niewczas MA, Biancone L. et al. Metabolomic Profiling in Individuals with a Failing Kidney Allograft. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169077 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169077

117. Kouidhi S, Zidi O, Alhujaily M. et al. Fecal Metabolomics Reveals Distinct Profiles of Kidney Transplant Recipients and Healthy Controls. Diagnostics. 2021;11(5):807 doi:10.3390/diagnostics11050807

118. Lan Y, Wang D, He J. et al. The gut microbiome and metabolome in kidney transplant recipients with normal and moderately decreased kidney function. Renal Failure. 2023;45(1):2228419 doi:10.1080/0886022X.2023.2228419

119. Wang J ZX, Li M, Li R, Zhao M. Shifts in Intestinal Metabolic Profile Among Kidney Transplantation Recipients with Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2023;19:207-217

120. Chiyu Ma ea. Intestinal microbiome and metabolome analyses reveal metabolic disorders in the early stage of renal transplantation. Mol Omics. 2021;17:985-996

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Swarnima Pandey, University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 20 N. Pine Street, Baltimore, MD 21201; Phone: (667) 677-0652; Email: pswarnimaumaryland.edu; p.swarnimacom.

Corresponding author: Swarnima Pandey, University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 20 N. Pine Street, Baltimore, MD 21201; Phone: (667) 677-0652; Email: pswarnimaumaryland.edu; p.swarnimacom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact